From the history about the mines at Litlabø

Mining 1865-1903

The first discovery of Pyrite at Stord was reported to the sheriff on October 10th, 1864 by Gotskalk Nilsen Evanger. He made the discovery on Rossneset at Litlabø. The next day, Tørres Dale reports findings at Nysæter. Several reports of discoveries followed quickly. Both at Nysæter and at Øvre Litlabø, they found large deposits of Pyrite that were located so that they could be operated in opencast mining. The deposits were also close to Storavatnet.

Mining operations at Nysæter and Litlabø are assumed to have started in 1865. The first years were the largest mines at Rossneset and Nysæter. From 1874 there was operation in Høgåsen. In the Nysæter mine, they struggled with poor ventilation in the large sink, and they finally gave up operations in 1874. In Rossneset, there were operations until 1875, with 25 employees in the last two years. Later, the mine in Høgåsen was the only one in operation. On the other hand, it was a very important mine and was in operation until September 1900. A number of other small deposits were operated for shorter periods. Many of the deposits were far from Storavatnet, which was the best exit road.

Det Bergenske Grubeselskab is a central name in this early period. The company was formally founded in Bergen in March 1866, but had been active all year before. Consul Peter Jebsen and civil engineer Nils Henrik Bruun from Bergen and lawyer Christian Fredrik Heidenreich in Stord were behind it. In 1866, the company bought half of Øvre Litlabø for 1260 special dollars. They were responsible for the operation of, among other things, the mine in Høgåsen. It was also this company that in 1876 started dynamite production at Litlabø, probably to speculate on the income in a time of poor economic conditions in the sulfur market. For a short time, there was also a Haugesund mining company in Litlabø. In 1867, Haugesundarane bought the second half of Øvre Litlabø. They operated with extraction and separation of Pyrite in one or another place in the area, but uncertain exactly where. In 1876, the Bergen Mining Company bought the Haugesund company's shares in Øvre Litlabø and was then the only remaining mining company on the farm.

An interesting feature of the mines on Litlabø during this period is that the owners were Norwegian all the time. Many other Norwegian mines had non Norwegian owners. In 1894, the mining company was sold to Stordøens Dynamit Compagnie, which in turn was owned by Nitroglycerin-Compagniet in Oslo. The company continued with both dynamite production and mining in Høgåsen, but things went downhill with mining. In the early 1890s, a new player also came on the scene. It was engineer Hans Olaf Lind who previously had been mining manager for Det Bergenske Grubeselskab. In 1884 he had sold out of the company, but since then he began increase his share into the company's rights. When the deposit in Rødkleiv was available, Lind was quick to secure the rights and to start a trial operation. In 1902, Lind received rights for all the old mines. In May the following year, he finally got to buy the entire Litlabø farm with the mines. Unfortunately, Lind did not manage to do much, because in May 1904 he died.

It did not turn out to be business like investors had believed in the mid-1860s. Unusually low sulfur content in the Pyrite meant that the owners at Stord struggled hard in the competition with Pyrite of better quality from both Norwegian and especially manufacturers in Europe. All ready in the 1870s, the pyrite mines in Spain and Portugal accounted for most of the world's production. The prices at Stord were under pressure, and operations were marginal. The company struggled to find deposits that were viable during the recession. In 1903, therefore, there was a halt to mining at Stord. The small mine that Lind had in Rødkleiv was the last one in operation.

In the years 1865-1903, a total of 108,909 tons of Pyrite was extracted from around 85,050 m3 of rock from the mines around Storavatnet. In his report, Chr. A. Münster mentions some of the buyers of the Pyrite in the 1880s. We see that Pyrite from Stord was exported to various companies in Gothenburg, Szczecin and Memel, in addition to the Norwegian Hafslund and Stavanger chemical plant.

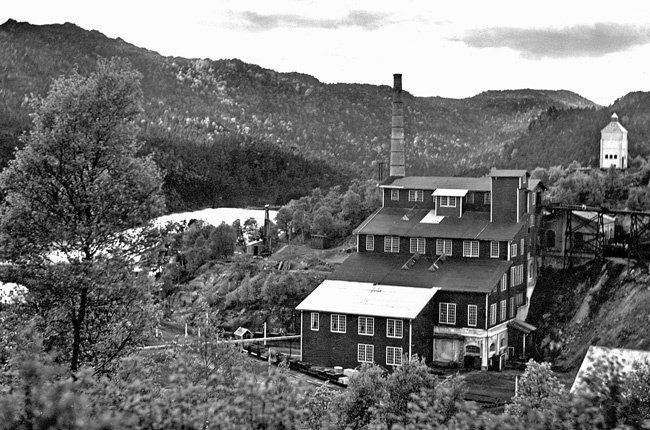

The Washery (prosessing plant) at Litlabø

A/S Stordø Kisgruber was founded

After 1903, mining at Stord stopped, but soon completely new, foreign, interests came on the scene. A financier in Antwerp, H. Fasting, had taken an interest in the Pyrite deposits on Stord and considered investing larger sums in the start-up of modern mining on the island. In 1905, therefore, on behalf of Fasting, mining engineer Christian Münster came to Stord to study the deposits in detail. Münster's studies ended up in a comprehensive report which he then sent to Antwerp in 1906. We can take with us that Münster saw a bright future for the Stord mines and calculated total construction costs for the entire modern mining facility to 600,000 kroner. Included in the amount were both incinerators with a large Washery, shafts with hoisting machinery, a large and modern quay with storage bunkers, and an electric railway from the mines to the quay.

With Münster's recommendations, the Belgian Fasting dared to put funds into the Stord deposits. All ready in 1904, Münster on Fasting's behalf had secured an option on the mines on Stord. Fanny Lind, widow of the mining pioneer Hans Olaf Lind, sold the farm Øvre Litlabø with all rights to Münster for 11,216 kroner. Fasting had also secured the property rights to several other Pyrite deposits in Stord, but also those in Münster's name, since foreigners could not property rights. In 1907, Münster then transferred all real estate and rights to the newly formed company A/S Stordø Kisgruber.

A/S Stordø Kisgruber was founded on the 11th February 1907. The share capital was NOK 300,000, and Fasting's company, Compagnie Minière Belge-Norvégienne, had the majority of the shares. On 17th of June the same year, Stordø Kisgruber was granted a license for mining operations. The Belgian company soon discovered that the construction work could not go as fast as anticipated, and far from as reasonable as intended! The technical ideas of Münster was followed, and these were largely successful. But on the economic side, Münster was far too optimistic. German capital was the salvation for the plant. In February 1908, an agreement was reached between Compagnie Minière Belge-Norvègienne and the German Zellstoff-Fabrik Waldhof. The German company received two thirds of the shares in Stordø Kisgruber, in exchange for providing NOK 300,000 in fixed capital. Waldhof was a large pulp mill with a high demand for sulfur. By securing ownership shares in the sulfur ore mines at Stord, they secured the supply of sulfur for their own consumption. Over the years, Waldhof came to invest almost 15 million kroner in the mines on Litlabø, but not a year did the Germans extract profits from their mining company. On the other hand, it was themselves who set the prices for the Pyrite that they sold to themselves! The co-operation between the Belgian and the German company basically never found proper form. In 1912, Fasting and his company withdrew from Stordø and transferred the remaining shares to Waldhof. Waldhof came to be the sole owner of Stordø Kisgruber from 1912 until after the last world war, only interrupted by a short intermission in the years 1917-1924, when Nordisches Ertzkontor in Lübeck had half of the shares.

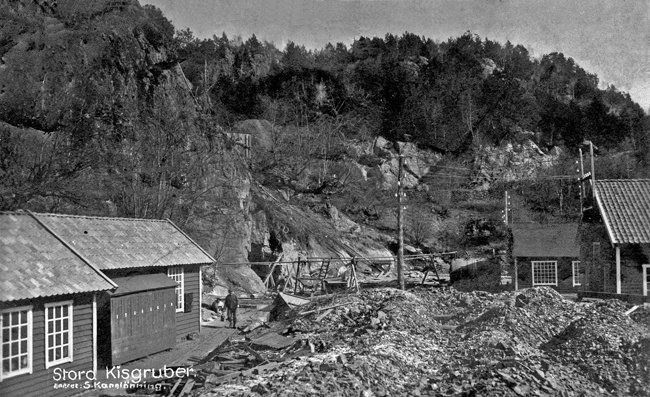

An early photo from the mine plane.

Stordø era under German ownership

The whole time while Münster was conducting exploration work, and since then while the construction work was going on, test operations were going on in the mines. In the spring of 1906, they stated that they had about 20 men at work. The following year, the workforce increased by 10-20 men. The official mining statistics for 1908 tell us that the main operation took place by mining in the Høgåsen. In the last half of the year, Stiger kontor, seven workers' housing and a country store with a bakery were built. The following year, there was also work in Høgåsen and the nearby deposit Sadalen. In addition, there was activity at Rossneset. Close to the mining tunnel to Høgåsen, the work to construct a shaft for the deep-lying floors had begun. Deposits at Nysæter, Rossneset and Bjørnåsen saw Münster as reserves. The other discoveries were all to be extracted by tunnels from the new shaft.

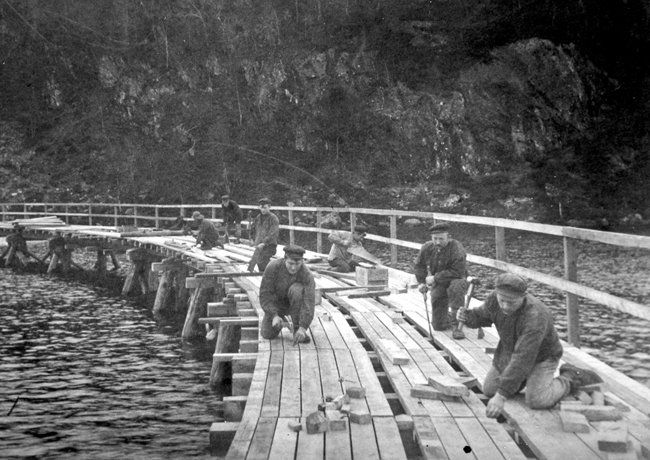

The annual report for 1910 stated that “The past year can be regarded mainly as a year of construction. In the mine work has been carried out to investigate the thickness of the ore deposits and to prepare for the demolition. ” Most of the construction work began in 1910. At that time, the shipping quay had been built, and at Litlabø the Washery building, compressor plant and steam plant was constructed. In 1911 they built shaft towers and houses for the elevator machinery, and at Grunnavågneset three bunkers with a storage capacity of a total of 6000 tons were built. Both railway, Washery and quay were put into trial operation in the spring of 1911, but stopped after a short time due to a labor dispute. The operations started again in September. The year of 1912 is often counted as the first proper year of operation, with a production of 20,000 tons of Pyrite. That was less than a third of the annual production Münster had expected.

The management at Stordø Kisgruber had many stuggles. The company had a tough financial start. When the operation started, it also seemed that the Pyrite was much poorer than Münster had calculated. The raw ore had a content of 22-23% sulfur, and 2.2 tons of raw ore gave one ton of export ore. It is said that no other mine in the world is run on such lean ore! For Stordø Kisgruber, it was therefore difficult to get sales and achieve good prices for the finished product. Another problem was the preparation plant itself. The Washery did not meet expectations and gave too little capacity. Several times this was attempted to be rebuilt. Only after a major renovation in 1938 was the management satisfied with the preparation plant. Despite the difficulties, the owner Zellstoff-Fabrik Waldhof never gave up the company in which they had invested so much. Over the years they adapted their own machinery to the poor Pyrite from Litlabø, and in the interwar years Waldhof was practically the only buyer of the Pyrite.

Only in 1926 did Stordø reach 70,000 tons of export Pyrite, which was the annual production Münster had calculated with. Production increased further, to around 130,000 tons before the war. In 1937, 124,259.6 tons of Pyrite. In 1938, the company had 329 workers and 38 permanent salaried employees.

Construction of the railway bridge from Litlabø to Holtangen. Photo approx. 1909

From open pit to mining tunnels

In the 19th century, most of the mines at Stord were operated as opencast mines. In line with Münster's plan, the new company immediately started underground operations. Stordø extracted ore from the vast majority of the old deposits, but approached these and mined with mining tunnels and drifts. In the first ten years, the mining took place from sole 2, ie from the same level as the drift. The shaft down to the deeper levels was started in 1911, but not in use. When World War I broke out, the pumps were brought up. For several years, the shaft and the third sole came to be under water, until in November 1920 they drained again and began to expand. Throughout the 1920s, more soles came into use. Through the years it developed into a spider web of mine tunnels, with the shaft as a kind of a center. None of the corridors should be particularly longer than one kilometer long, but they went out in all directions. In 1965, the total length of shafts and drifts was at a total of 8.25 miles! The elevator shaft reached down to the 16th sole, 720 meters deep.

Down to the right the old shaft tower, in the middle of the picture to the left of the office, in the background the Washery.

The mines after world war II and the State as owner

The mines at Litlabø were in operation for most of the last world war, but had to stop operations after a British-Norwegian raid on the night of 24 January 1943. The fact that the Pyrite was exported to Germany was an important reason for the sabotage. Several explosive charges went off in various buildings on Litlabø, and among other things, both the hoisting machinery, the compressor house and the locomotive shed were blown up. The attack led to a halt in production until 15 March 1943, but the aftermath was long overdue and delayed production greatly. Especially because off that the elevator machinery was destroyed. The old elevator was still intact, but was in poor condition and had far too little capacity.

A/S Stordø Kisgruber was reported as hostile property in June 1945, and in October of the same year the Directorate for Hostile Property decided to close down operations. Later, the Directorate changed its mind, and regular operations were recorded from September 1946. The Norwegian state then bought Stordø Kisgruber and was the owner from 1 January 1948. The purchase price was one million kroner. At the same time, all debt to Germany was cleared, no less than 5.8 million kroner! Thus, the financial basis for further operations was well laid out. At the same time, the company had large ore reserves to extract. During the war years, more effort than necessary was put into research and an unseen amount of gray rock was blown out. It was a well-covered form of war sabotage. When the war was over, large clean layers of ore were ready to be driven.

In the post-war years, various modernization work was carried out and a whole lot of new material was purchased. Among other things, the crushing plant was rebuilt, the shaft was expanded for new and larger mining wagons, the old steam power plant was converted to oil heating, the quay received diggers, the mine received nine new loaders and new accumulator locomotives, and the Washery received a new flotation machinery. The throne of modernization had manifested itself over several years, but the war had delayed the work. Some equipment was worn out and outdated. Other equipment had to be renewed simply to improve production capacity.

The period 1947-1960 is often counted as Stordø Kisgruber's golden age. The export market for Pyrite was very good during this period, and then Stordø managed well with its normally uncompetitive Pyrite. It was important that the old Stordø owner Waldhof in 1950 again registered as a large buyer of Pyrite from Litlabø, and continued as a customer for another fifteen years. In 1948, production was 7,360.9 tons of sulfur pyrite with 41.2% sulfur and 51631.5 tons of washed pyrite with 39.2% sulfur. In the same year, 39,545 tons of shingle were sold. Until 1965, a total of 7.53 million tons of raw ore had been mined. Of this, 3.32 million tons of export Pyrite had been produced.

Electric locomotive with ore wagons in front of the laundry at Litlabø. The photo is probably from approx. 1950

The big change in the last hour

Towards the end of the golden age, the company noticed more and more that the production facilities were old and dilapidated. In 1959, operations stopped so often due to repairs that it led to significant failures in production. At the same time, the entire mining industry experienced a large and rapid decline in the prices of Pyrite. In Stordø's case, the expenses per ton of ore were greater than the income from and including the year 1959. The company was therefore in deficit. Increasing access to clean sulfur down on the continent was the reason.

In the autumn of 1963, the board of Stordø Kisgruber presented three alternatives: To stop operations as soon as possible, continue to run a deficit in the hope of better economic conditions, or make the business competitive. The board went in for the latter option. They wanted to keep production at 70,000 tons of ore a year, but with a reduced workforce. To achieve this goal, NOK 4.5 million had to be invested in shafts, lifts, treatment plants and loading facilities. The Ministry of Industry and Finance, for its part, was skeptical about whether Stordø would achieve the desired productivity. The following year, a new board presented a new modernization plan. This one was much more pessimistic than the first one, which was withdrawn. Another year passed, and then an updated plan was presented. The board did not see that the totally dilapidated preparation plant could go through the whole year 1966. The ministry waited until then to accept the plan to see how the price development went, but in the end they approved modernization.

The major reorganization took place during the joint holiday in 1967. The changes came in the Washery, where all machinery was newly installed, with the exception of two crushers and the flotation department. All the old set machines were replaced by four new strap jigs. The railway was torn away and the route turned into a road, and a bogie trailer took over the transport down to the quay, where a wheel loader replaced scrapers and conveyor belts. In total, it was modernized in 1967 for three million kroner.

The mining area around 1950.

The closure

The extensive modernization of the transport road and the preparation plant had gone well, but led to the need for modernization of the other parts of the plant. In between, the 30-year-old Scheide facility was in very poor condition. Further necessary improvements were estimated at about NOK 2.2 million. At the same time, it was even more difficult than before to get a deposit on the ore. In the autumn of 1967, the price level was significantly above what it had been only two or three years earlier, but it was difficult to sell the product! In 1968, most Norwegian sulfur ore producers experienced major marketing difficulties. Stordø's by far largest buyer, Waldhof, also gave definite notice that they would not need more Pyrite, due to the fact that they were going to change operations. Active work to check the market gave poor results. There were poor prospects of selling the ore, not only in 1968, but also in the long run. Stop was inevitable in the end. The argument against a complete halt was that the market could change and that all the modernization work carried out would be completely wasted. In addition, Stordø was considered an important workplace.

April 30, 1968 was the last day of ordinary operation at Stordø Kisgruber. The production of shingle continued for some time to come, by crushing rock from the waste rock tip in Hustredalen. During 1969, 52,000 tons of shingle were produced, but in January 1970, this part of the business also came to an end. Then there was no more usable stone. It was considered to start new shingle production with a new or modernized plant, but it was found that the shingle prices were too low for it to pay off. A few thousand tons of ore were stored on the quay, but were finally shipped in June 1970.

The intention was that the mining equipment should remain intact until further notice, until the mine's future was clarified. In the end, one had to realize that it was not easy to get new industrial operations to Litlabø. It was probably only the ore deposits that pointed out Litlabø as a natural industrial city. From October 24, 1969, the clearing of the mines was suspended.

In the end, Stord Verft was the only one who wanted to buy the mining company. They wanted to add sub-industry to Litlabø. A contract came to the table, but then the majority in the municipal council found that the municipality should exercise its right of first refusal. It was a narrow majority that decided the case, after voting at a total of four municipal board meetings, many exchanges of opinions and an urgent newspaper with engaged newspaper articles. On 2 December 1972, Stordø Kisgruber was formally taken over by Stord municipality. Throughout the 1970s, the municipality rehabilitated many of the old factory buildings. Both Washery, scheide building and crushers were demolished, as were many of the old workers' houses. Residential houses that were seen as usable were sold to private individuals. Commercial businesses have been given space in the adjoining larger buildings.

Text: Per Ivar Tautra